Decolonizing seeds and protecting diversity in the seed sovereignty movement.

Gosia Rokicka: You are a Seed Keeper — that’s a pretty cool job title. Can you tell us more about what you do?

Rowen White: I come from a place called Akwesasne, which is an indigenous Mohawk community near the Canadian border. Traditionally, we are an agricultural nation so caring for seeds and for the Earth in general aligns with our cultural values and has been handed down from one generation to the next over millennia. There’s a lineage of people cultivating relationship to their food and to the Mother Earth. We have quite a number of heritage and traditional varieties of corn, beans, squash, sunflowers, tobacco and other plants that have been specifically handed down through many generations over the last several thousand years as a part of our traditional food ways. I have the great honor of being one of the seed keepers of the Mohawk people which means that, together with others, I am making sure that the seeds stay alive and healthy and that they’re given freely within our community, as well as passed down to the next generations.

Sounds like a true passion.

It is a real passion. Due to the impacts of colonization and acculturation many of native North American food systems have been dismantled and unfortunately, they are not a part of our everyday life anymore. As a teenager I didn’t really have access to a lot of the traditional foods and to the cultural memory that goes with them. As a young woman I became interested in traditional farming and wanted to learn more about where our food comes from and to create more sovereignty and freedom through cultivation. That’s how I opened this Pandora’s box of the world of heirloom seeds… and wow!

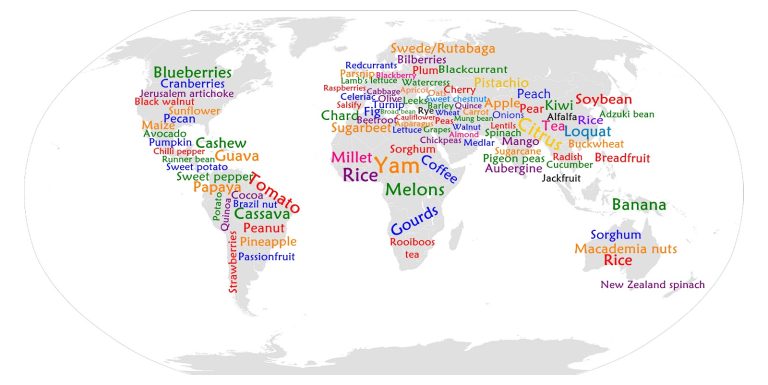

It turns out that not only do seeds have this incredible diversity — a prism of different colors and shapes and sizes and places where they grow best and communities that they come from — but that they also carry stories and beautiful lineages of relationships.

For Mohawk people agriculture was historically at the center of our culture and I was very curious why it no longer was a significant part of my life and how I could reengage and restore that relationship and connection to the land. So I began to ask people, gather seeds and learn more and more about my responsibility to care for them. It led me on a 20-year-long path to being a seed keeper. Being an educator and a mentor constitutes a central part of this role. I am helping people who are in a similar situation I was 20 years ago — curious but not having access to knowledge or seeds. I am passing this knowledge I received from the elders and mentors of mine within the community because I honor the importance of keeping these traditional seeds alive together with the cultural memory that is attached to them.

Busy life!

It is. I run a seed co-operative. We have a 10-acre farm that focuses on stewardship of seeds and education of people about seed care and growing food in holistic ways. I am also the national program coordinator for the Indigenous Seedkeepers Network — a program of the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance, which works with a number of different tribal communities to create seed libraries and banks and also to build mentorship networks to leverage resources around policy for protecting our seeds against biopiracy, biocolonialism and patenting. I travel all over North America to see tribal communities and facilitate workshops and conversations around how communities are creating these resources in their lives. So that’s my work in a nutshell. It’s complex and multilayered but it’s also a beautiful path to follow. The seeds have guided me well along my path.

So would you say that seed keeping could be seen as a decolonization movement?

Absolutely.

To me decolonization is the foundation of the seed sovereignty movement. But I also like to put a positive spin on it: it’s re-indigenising.

We are claiming back our traditions and rehydrating those original agreements that we had with the plants and with our ancestors but also with our descendants. It doesn’t happen only in Native American nations. Across the globe communities start to recognize the importance of durable, resilient, local food systems. Local engagement has been growing the incredible momentum in the last several decades. The Seed Freedom Movement is a part of it because we recognize that we cannot have a durable and resilient local food system if we don’t have locally adapted seeds that are a part of it. Seeds are the foundation of agriculture but they also encode a memory of the land, the climate, the weather, as well as people’s cultural values, aesthetics and stories. And now people of all generations are coming together to recognize the importance of seed heritage, to create new ways to counteract the globalization and industrialization of our food systems, to resist monocultures. At the heart of what I do is the creation of the seed literacy. Even if you’re not a farmer or a gardener, seed is a vitally important thing in your life because we all eat.

Among Mohawk people the women were traditionally responsible for seed keeping. Is it still the case within this modern growing movement?

Historically in most cultures — although I can confidently talk only about the Mohawks — seeds were considered feminine. It relates to our own reproductive system — it’s the woman who carries the seed. If you look botanically, it’s the female part of the plant that is creating the seed, so this is a feminine expression of the plant’s life cycle. In our tradition and in many cultures and traditions across the globe seeds have traditionally been considered a feminine aspect of the agricultural system and largely it’s been the responsibility of women to care for them.

In your writing you are using this beautiful word — rematriation.

We’ve been using it in a lot of different contexts. Primarily it’s about restoring the feminine back into our lives through our food systems and recognizing that many of the industrial global food systems are very patriarchal, so it’s about creating that balance. Our traditional knowledge wasn’t about women being more powerful than men or the other way round. The point was to maintain that egalitarian balance between the masculine and the feminine.

Rematriation in relation to seeds is about bringing the seeds back home into their original context and into their communities of origin. Speaking more broadly, rematriation is about restoring that feminine energy back into our lives and our communities.

I learned of the word through a man named Martin Prechtel. In my latest blog post I quote a piece from his book “The Unlikely Peace of Cuchamaquic” — he speaks very eloquently about the idea of rematriation, about that holy feminine being restored back into our lives. Among native peoples we talk a lot about repatriation of things back into our communities. So in this case we decided to use a more feminine word. It’s inspired by the work of Martin Prechtel but also by the legacy and lineage within indigenous communities.

Is it relatively easy to engage young people in such work?

For many years there had been this generation gap. Older people were keeping traditions and seeds alive but younger ones didn’t engage, didn’t see it as relevant. But now I’m witnessing a resurgence of the movement among the younger folks in tribal and farming communities but also in a more mainstream culture. People are waking up to the fact that the monocropped way of life and industrialization of everything is damaging not only to the nature but also to our relationship with the world. Young people these days are inheriting a world that is deeply troubled. In a way they know they have to do something and they are enraged. Stewarding seeds is such a powerful, beautiful and inspiring path to follow. It’s a hopeful form of activism. It’s very tangible and it creates something positive to work for instead of working against something else.

We have to be good future ancestors and responsible descendants, so it’s our responsibility to care for the seeds to make sure that younger generations and future generations that we might not know yet have them.

I have a teenage daughter who’s been growing up on a seed farm so this way of eating is her life from day one. She has a great passion for the culinary arts. She wants to be a chef. There’s a spectrum of ways in which young people can engage in this kind of work. If you’re interested in farming or gardening, that’s great but you might as well be a chef, an artist, an activist, a public speaker. There are many different ways to contribute. A lot of our work in the seed sovereignty movement evolves around inclusivity — how we can acknowledge the gifts that different people can bring to the table and how to make sure that a well-rounded resilient food system has many people contributing in various creative ways so it’s not only about growing food.

You also say that seeds are living beings and our relatives. Can you unpack it a bit for people who haven’t grown up within a Native American community and may have a problem with relating to it?

Sure. All of us — and that includes everyone who is reading it now — descend from a lineage of people who had a very intimate relationship with plants. It’s just in the last couple of hundred years of human history we’ve been looking at seeds and food in general as a commodity as opposed to something that was an integral part of our life that we shared. It used to be a commons, a collective inheritance. A long time ago our ancestors — mine, yours, everyone else’s — made agreements with plants that they would take care of each other. There is this intimacy, there are familial relationships that are encoded in creation stories that are held within many different ancestries and bloodlines.

So when I say that seeds are sacred because they are living relatives, I mean it wholeheartedly. That’s how I view seeds and that’s how pretty much all of humanity saw seeds up to a certain point.

Then it started to get industrialized and commodified and our collective view of what seeds represented has changed. I like to remind people that 200 years ago in the United States and in Europe there were no seed companies. People shared and traded seeds instead. I like to tell people to think deeply about their relationship with their food and with the seeds that make this food. If you trace back different cultural lineages, you’ll see that plants and seeds played significant roles in cosmologies and worldviews. In the Mohawk creation story such foods as corn, beans, squash, sunflowers and strawberries figure prominently. They grew from the body of the daughter of the original woman as a gift to her sons. These foods would then sustain them for the rest of their time here on Earth and they literally grew from her flesh and bones. So in our cosmology we see them as our relatives. We have an agreement with them that they would nourish us every day but we have to give back. That’s a reciprocal relationship.

So now, in North America but also globally, we need to rethink and rewrite the narrative of our relationship with food and seed. At the moment there is a dominant narrative in the Western world that sees plants as dead inanimate objects that we just grow, harvest, mechanize and exploit. But that dominant narrative is really just a shallow facade around a much deeper relationship that humans have had with plants for a lot longer. So in our educational seed co-operative Sierra Seeds we challenge that dominant narrative.

This is a radically different view to the one held by mainstream agricultural companies. You are promoting it now not only through Sierra Seeds in the US — recently you joined the faculty of over 40 women who teach the Permaculture Women’s Guild Online Permaculture Design Course where you run a module on seed keeping. It is not a regular part of the PDC curriculum, is it?

It isn’t indeed. Permaculture is a fantastic curriculum and a beautiful pedagogy — a wonderful system of knowledge that has been distilled down from a much larger traditional ecological body of knowledge originating all around the world and I think many of us within the movement acknowledge that. There is a very particular curriculum of 72 hours of teaching that accompanies the PDC and seed stewardship isn’t a part of it but then… how can it not be a part of it? Seed stewardship should be an integral part of every farmer’s garden and it was — until a hundred or two hundred years ago. So when we’re talking about permaculture and creating holistic food systems, the seed has an inherent place within it. People need to know how to steward seed and how to cultivate seed that’s regionally adapted to a very specific place and to their own unique low input permaculture system. So I approached the creators of this course and said: “Hey, what if we include a module on holistic seed stewardship?”.

The seed is the beginning. It’s so vitally important to the foundation of all food systems but at the same time most seeds available now aren’t adapted to low input polyculture or permaculture systems.

They have been bred and selected for monoculture in a very different farming system. That’s why I think that for people who are meant to obtain a certificate in permaculture design it’s important not to forget about saving seeds. I feel super thrilled to contribute to this course and hold a little corner of that space to really honor the seeds and all that they give us.

One more thing… I’m sure that everyone who got to this point of our conversation feels like me. I buy the majority of my vegetables from a local farming co-operative so the veggies I eat are local, culturally appropriate and organic. But as a city dweller with a small garden I throw away most of these really good seeds and now I feel super-bad. Any advice for folks like me?

The beautiful thing about this growing seed sovereignty movement is that there are many different community projects and initiatives that are springing up wherever people come together to think creatively about how we can develop more access to good seeds within our communities. So in a lot of places, especially in urban environments, there are seed libraries and seed exchange — places where people help to facilitate the distribution and collection of these seeds. So I would recommend that folks, who don’t have a lot of capacity in their life to do a lot of seed stewardship in their own garden or allotment, connect with the wider community. Seed libraries are popping up — it’s worth to look for a local one and share your surplus of seeds there.

The beauty of a seed is that it multiplies exponentially. It is a wonderful example of the natural abundance of the Earth and I think it is also a beautiful expression of the gift economy. Even keepers like myself always have more seeds than we need. It inspires me to be generous and to give seeds outside of my own home farm. The seeds teach us to be generous and to share our abundance with other people and this is really the true nature of things. We live in a society where the dominant narrative is based on scarcity and austerity, so we need to start paying attention to seeds because they remind us of the inherent generosity of the Earth and of our own inherently generous nature.

To find out more about Rowen and the projects she’s involved in, have a look at the Sierra Seeds website. Rowen is also one of the tutors in the Permaculture Women’s Guild Online Permaculture Design Certificate course.

Keep reading…

On placemaking, true diversity and intercontinental cross-pollination: a conversation with Ridhi…

“There are geopolitical forces at play that make different types of knowledge weighted unequally.”medium.comOn urban permaculture, eco-activism and co-creation of space with non-human animals – a…

“We put up fences to mark what’s ours and what we want to keep out but it doesn’t work for non-human nature.”medium.com