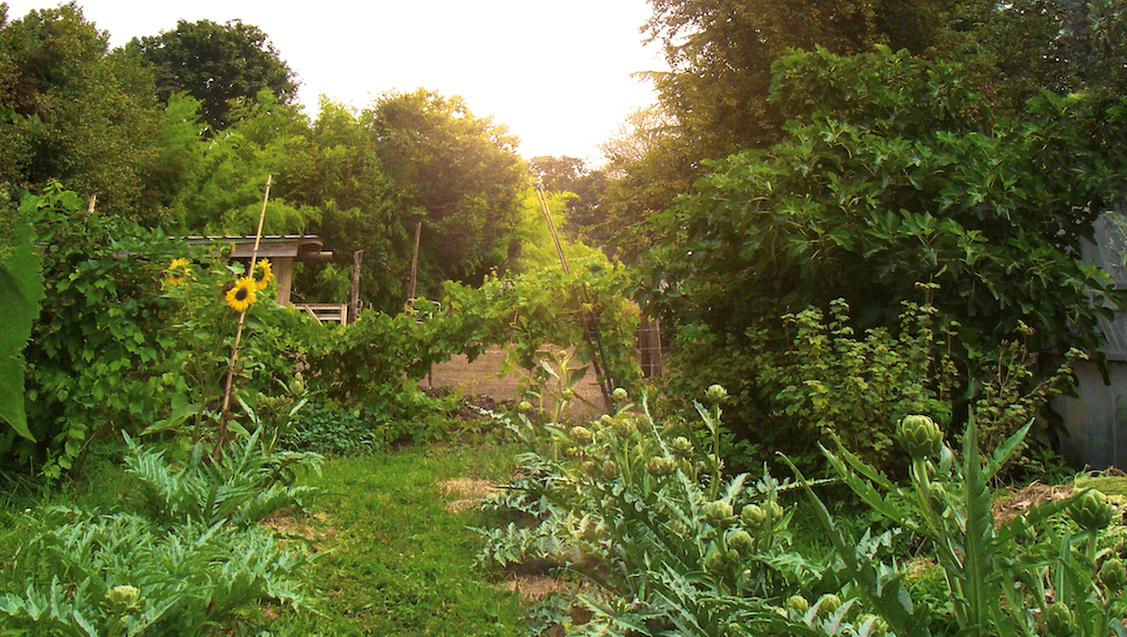

At Emergent Abundance Farming Collective, we grow both annual vegetables and perennials in a diverse landscape on approximately half an acre of land. The land came with a challenge: the presence of Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense).

In the power-over paradigm of our dominant culture, the presence of thistle can’t be tolerated. I can hear the voices in my head: Eradicate ALL weeds!! As we use a minimal tillage approach and no herbicides, I might at this point in our short history on this land have thrown up my hands high in the air – and given up.

Instead, I decided to ask questions.

What if I asked the thistle what it has to teach us?

What if I asked myself to shift my mindset? What if I didn’t call the thistle a weed, but a perennial cover-crop? What if I looked at the thistle as a living mulch plant much like comfrey which we plant intentionally in permaculture settings?

What if I took the time to observe and evaluate what the issues actually are, case by case, crop by crop?

So, what are the issues of having thistle present in a field? I can see mainly three problems: Thistle outcompetes many crops for light. Thistle outcompetes many crops for air-flow (which is a pretty crucial element in the humid summers of the mid-atlantic US). Thistle also spreads quickly into new territory, covering the soil in dense patches.

Thistle is known to be a healer of soil. It is said to disappear once the job is done. As I am a migratory farmer, I have not had the honor to be in the presence of the same land long enough to be able to verify this statement. But I am assuming that it may as well be true. And I can also deduct from it, that even in a shorter time-frame, a healing effect will be experienced.

In my observations, annual vegetables thrive in fields that are inhabited by thistle. My sense is that the way thistle interacts with the soil creates a perfect bacterial-fungal balance and pH in the soil to promote vegetable growth.

There is more: as a perennial cover crop, thistle maintains microbial soil life by actively penetrating the soil with its roots, feeding microbes on its root-surfaces. Thistle continuously sinks carbon into the soil. Thistle promotes good soil structure, the absorption of water and the availability of air in the soil. Thistle is an engine of biomass production, which can be used right there in the field as a mulch further feeding soil life. Thistle taps deeply into the soil bringing up nutrients. Thistle is rich in silica which contributes to general plant health.

Then there are other effects, such as an early infestation with aphids on thistle which in turn invite the beneficials to the party: last year our field was buzzing with ladybugs, parasitic wasps, gall midges and lacewings by early May. From then on, we didn’t see a single aphid outbreak on any of our vegetables – while other farmers in the area had their share.

And then there are the more personal teachings: thistle tames my ego, softens me, allows me to move out of the power-over paradigm into a power-with mindset.

Befriending the thistle, with its abrasive texture, with its spines in the tips of my fingers, invites humility into my soul and into our garden space.

Since the issues stated above are real, the thistle clearly needs to be managed if we expect any yields from our vegetable crops. We can do this in a way that we can reap its benefits while managing the more problematic aspects of its presence. What exactly needs to be done, depends on the crop and the timing.

Taking the fava bean as an example. The fava bean is a fast growing sturdy plant, with large seeds that are seeded early in spring. We seed no-till, maintaining the integrity of the soil. The presence of small, re-emerging thistles creates a protective microclimate that aids the germination and protects the plants in the cool nights of early spring. When the thistle starts to outgrow the fava bean, we go through, topping the thistle with gloved hands, leaving the leaves in place to decompose. These provide nutrients to the beans and excellent soil microbial food – maintaining a beneficial bacterial-fungal ratio in the soil. This will have to be repeated every few weeks throughout the growth of the bean plants until the beans are large enough to outcompete the thistle. The work is thereby distributed relatively evenly over the course of the crops life, never requiring any back straining digging or hoeing.

For smaller plants that germinate slowly – such as carrots, it seems more appropriate to try and remove the thistle more deeply with as much root as possible – giving the carrots a head start. After that, the same method can be used as described above with the fava beans.

With respect to the third issue listed above, the ability to spread wildly into dense clusters, covercroping to provide continuous competition is very useful. The aim is not to completely eradicate it, but to keep it manageable. This is an important difference. We can accept the continuous presence of thistle in the field, fluctuating in intensity in different parts of the field throughout the years. Once thistle is present, if nothing else is planted, thistle will take over, completely dominating the land, covering the soil, claiming all. But if we seed winter rye or a clover, the thistle will still be there, but sparsely. Here and there, not spreading, not dominating.

The thistle becomes our friend, stepping in when we neglected the need for covering the soil, offering food and sustenance to many small life forms.

I am grateful for this fecund teacher – patiently helping me to integrate my thinking and my farming practices into more holistic, earth-loving, life supporting ways. And – honeybees and butterflies are grateful for the blossoms, too.

Julia Smagorinsky (“Yulia”, pronouns kin/she) is a farmer, mother, permaculture designer, writer and facilitator in the Work That Reconnects Network. Yulia is a cofounder and director of Emergent Abundance Farming Collective and the owner of Widening Circle LLC – offering consulting services, classes and workshops to build community resilience and deepen our connection with nature.