The time I visited the oldest ecocommunity in Spain

By Elena Pollen

Long before moving to Spain, or, a few months actually, my partner & I came across this article about the oldest ecocommunity in Spain. Filled with beautiful pictures of wooden houses and wisened people, we dreamed of someday being there, living the self sufficient mountain life.

Two years later, having just arrived in León on foot, 130km of steep terrain and mist behind us, we were quite happy to get the bus to our next destination.

Matavenero, the oldest ecocommunity in Spain, is located somewhere in Astorga, which is another 50km from León’s centre. In July heat with not much tree cover, the walk was not appealing. Blablacar came to the rescue, and we were picked up outside the jumbo sized Gadis supermarket that I’d thought was exclusive to Galicia.

The man is the passenger seat was very talkative, telling us his opinion on Matavenero and giving us a quick overview of how it all started. The driver was quieter, and less enthusiastic about the hippie community. He later gave us the following review: “bla bla bla, paz y amor, bla bla”.

Yep, that pretty much sums us up.

From Bembibre we got a taxi to San Facundo.

On Thursdays there is a bus service primarily for residents but we arrived on a Tuesday. The taxi driver gave further additions to our still hazy imagination of the village, overall very positive and supportive of the project.

Matavenero was born from a Rainbow gathering in the late 1980s, mostly German adventurers looking for an abandoned village to reclaim and refill with lives less draining on the earth’s resources.

Free of strict rules and regulations, the base idea of the community was to live free of the world obsessed with money and power, and return to a land in harmony with nature and freedom.

The talkative taxi driver dropped us off at the bottom of the mountain in San Facundo. Torn between taking a dip in the natural swimming pool right there or braving the hike up to Matavenero, surprisingly we chose the latter and called on our camino-strengthened calves to carry us up there before sunset.

My partner got stung by a bee along the way but the heat and steep climb helped to distract from the pain. We went up and and up and up through a forest, then down down to a river pass, then up once again to finally reach the village on a mountaintop.

There we met Mirusz, or ‘Doctor Drums’ (18:41), a lovely Polish guy who had lived there for 25 years. He kindly explained a lot about the community to us and answered many questions, undoubtedly ones he’d been asked a thousand times before.

We stayed in the local albergue, an old house under the communal library with a kitchen and dining area and some large wooden bunks. It was quite unkempt but that could only be attributed to some of the fleeting guests who slept there.

A broken window had been left open and a spiky bramble had started to creep over the stack of dirty dishes by the sink. However, to have a free space to sleep and make food at the top of a mountain is a luxury, and it was at our own discretion to tidy it if we wanted to stay longer in comfort.

The rest of the inhabited houses looked beautiful and homely, mostly made from ruins of the old village, built upon with natural materials and unique style.

The house we slept in was actually the best of the ruins, which was why it was originally chosen to be the village school. The library was still in great condition with many books in at least four different languages.

That night we ate aubergine pasta and drank red wine with the other people taking refuge. Some people were there for experience, some -seemingly- for escape.

Two Russian girls clung to eachother like conjoined twins, and a skinny teenage guy flopped somewhere between moping and high energy. Another visitor, a French man with an owl as his spirit animal, had visited many times before and knew a few of the residents quite well.

The next day Mirusz had told us to meet at 5pm for berry picking, as part of the communal labour effort. The village was quite small and we’d woken early with the sun so weren’t quite sure what to do with ourselves til then.

We went to the old dome which used to be the hub of community life and did yoga on the dry grass overlooking the mountain range.

We ambled through the mismatching houses and paths lined with ripe guindas, sour cherries.

The old bakery near to the albergue and library was well refurbished with stainless steel worktops and a huge wood oven.

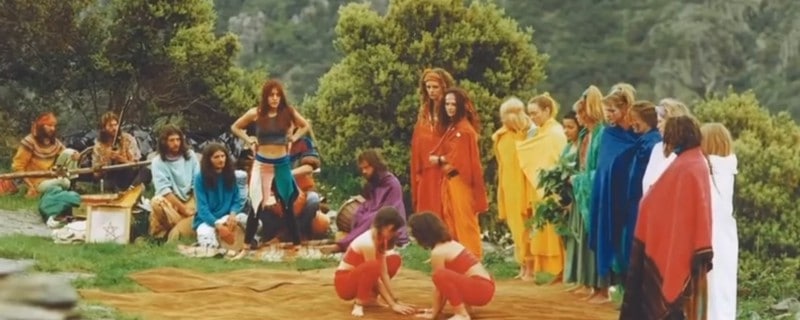

Living in this space was an old Filofax filled with original newspaper cuttings from when the community first started up. Beautiful people in colours of the rainbow holding hands in a circle.

People in wooly hats building houses in the snow. Articles about the initial search for a location, lists of abandoned villages for sale in 1989.

It was still early when we’d finished our little explore of the village, so we decided to pack our swimming stuff and make the most of the natural swimming pool back in San Facundo.

There we met Hannah, a tall and thin German lady standing laughing at us shivering in the freezing black water. We got talking about Matavenero, and it emerged that she had been one of the founding members along with her late husband, who died tragically saving people at sea.

She invited us for dinner and to sleep at her house, a welcome option compared to the fly infested albergue, but also a once in a lifetime opportunity to connect with the voice of a movement. We hiked back up to the pueblo, and Mirusz was visibly disappointed that we hadn’t shown up for the labour day.

We felt guilty and apologised, telling him that we’d met Hannah at the river and that we were really grateful for his hospitality. We hugged goodbye but couldn’t help feeling bad as we left feeling as though we had let him down. Maybe because of our enthusiasm we’d seemed as though we might stay longer, become residents and restart the original dream or something, maybe it was just a bad day.

We can only speculate.

We arrived at Hannah’s house to find she wasn’t there. After waiting on a nearby bench for half an hour we decided to wander further and see if any of the neighbours could give her a call, it was already about half nine. Some people higher up in the village rang her phone whilst we sat on an old sofa in their back garden, Hannah didn’t answer and we started to worry that we’d done the wrong thing.

Eventually, she called back to say she’d been visiting a friend in hospital and would be back soon. We met back in her house and talked at length about how the community started, her thoughts about its progression, why she decided to leave.

That’s one conversation in my life I wish I had recorded. Her sitting there against the limed walls reaching into her memories of thirty years ago, young and free and in love.

We slept in a light and airy room with an enormous cheeseplant towering across the ceiling. Hannah came down in her underwear and Nik asked if she’d forgotten we were here, to which she looked confused. We English are so prude.

In the morning we had madalenas and coffee and Hannah dropped us off at the bus stop. I got talking to a Danish woman who lived in Matavenero’s neighbouring village Poibueno, and we wished we’d stayed a little bit longer.

Bembibre’s bus station café was superb, and we got a few last words in with another older resident, who apologised for declining our dinner invite, saying it was due to the ‘other atmospheres’ present in the albergue that night.

I am in no position to make any kind of all-encompassing comment about Matavenero. I was grateful for the freedom to be able to walk up and visit, only time could create any kind of accurate assumption of the village, but even then it would be purely subjective. Many people are happy there, some feel it’s lacking, not what it was. Ultimately, it is a home for humans like any other village, and their individual privacy should be respected and maintained.

It’s inspiring just to know that a place so open exists, where one can try to live a life closer to the earth without government or electricity bills. Maybe someday I will go back and form a deeper understanding.