Design thinking, be intentional and present with your process.

When we’re embarking on a new design project — whether we’re working with a raw piece of land, infrastructure, a marketing campaign, or a social or economic system in our region — the temptation is usually to jump straight into the design process. We often begin with protracted and thoughtful observation and assessment of the existing conditions of the site or system in question. But we rarely pause to observe and assess our own current condition, the state of our mind — all that we are unconsciously bringing to the process.

Incorporating the cultivation of our ‘“Designer’s Mind” into our design practice allows us to harnesses the power of engaging clearly in an interconnected way as we use design models and processes. I’m not just talking about the brain. I’m speaking holistically. Without whole-systems introspection and integration, and an awareness of the state of mind, our designs will be restricted and fragmented by day-to-day distractions, attachments, objectification, unconscious conditioning, limiting beliefs and unresolved traumas (personal and collective).

Design means being intentional and present with your process. Having a realistic appraisal of the current moment creates authentic connectivity. The groundedness in and acceptance of what is, precisely and intrinsically, is the foundation for any change. In that sense, the starting point and ongoing practice of a designer are to be present, centered and connected before, during and after taking action. Routine reflection and observation keep us linked to the present moment and train us to realize emerging opportunities and constraints. These points of consideration also help us keep tabs on who and what is driving the design.

After 24-years of serving as a professional designer, I stand firmly by the notion that we can not navigate or effectively apply design models without skilling up in intra/interpersonal tools and practices. I’ve committed the last 15-years of my career to training hundreds of designers, mentors, facilitators, healers, and leaders, to navigate the present-day chaos and eco-social challenges, by responding in a regenerative and integrative way. What follows summarizes some of the insights I have gained through this work.

Design and Decision Making

A person who takes part in using an active process, or intends to make decisions is a designer. Anyone involved with a project is an inferred decision maker, project manager, and designer by default. However, an actual design requires conscious choices and mastery of being in the present moment. Working on an assembly line in a factory might not include design choices, however, preparing a meal in your kitchen comes closer to a design endeavor. Whether or not the designer is conscious of the tools and processes or explicit about them, affects the degree of engagement, and the outcomes. A person who intentionally implements designs, especially one who consciously creates forms, structures, and patterns is a conscious designer. To me, it seems that all our most basic decision-making processes include some level of design.

Let’s delve deeper into what makes a designer. For example, is it possible to sometimes design without thinking? Does the act of doing without thinking include a conscious choice that resembles a design decision? I sense that it doesn’t. Decision making alone doesn’t equal active design. Our brain functions in a manner to make decisions without our conscious engagement. However, it is true that design mimics our brains natural process.

These questions led me to research how we make everyday decisions. According to Susan Perry — in an article called Decision-Making in the Society for Neuroscience — the process is seamless, and we are unaware of the complex mental functions happening. In scientific terms, sensory data enters neural circuits in the brain. The brain cells compile and weigh the evidence to form a decision. Neurons perform these calculations. When a choice we make doesn’t have the effect we wanted, the orbitofrontal cortex activates and alters our behavior immediately, or the next time we collect similar data. According to this article, most decision making is automatic.

Thomas Saaty, a Professor at Katz Graduate School, writes, “In contrast with conscious decision-making, there are numerous subconscious decisions that we make without thinking about them. Some are biological and are made by different parts of our body to keep it alive and functioning normally. Others are a result of repetition and training that we can then do without thinking about them.”

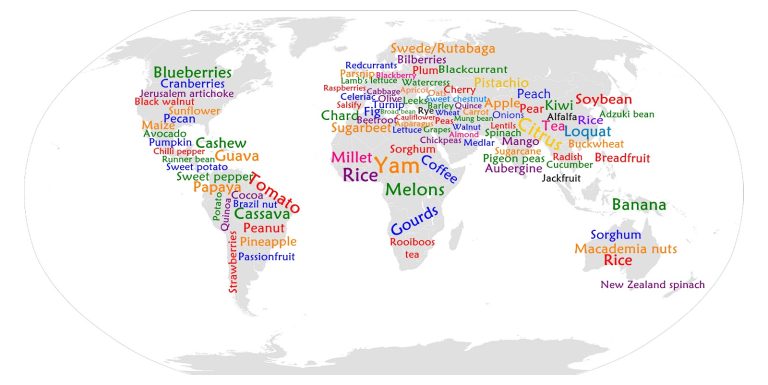

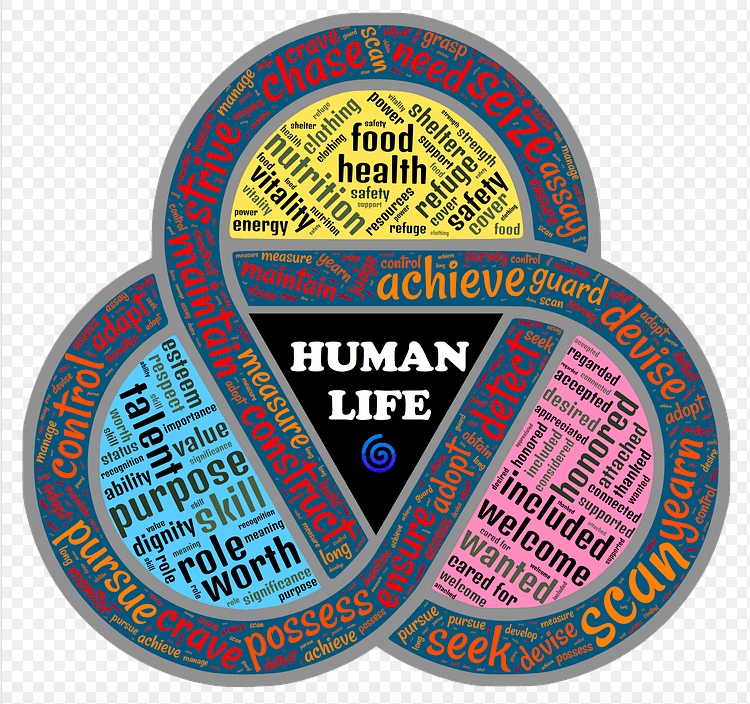

What, then, affects our automatic decision making? According to reports on Cognitive Psychology, numerous influences impact our decisions: instinctual needs for survival, presentation of choices (often manipulated by propaganda that influences our perception of needs and senses), societal norms, and learned behavior. We have necessities like food and water that impact our behavior as we pursue them. Looking at Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs, we also know that higher needs exist, such as “self-actualization” and a desire for personal fulfillment.

When we look at the factors shaping our sense of need fulfillment, it turns out that motivation is what drives human behavior. The article on Dynamics of Personal Motivation proposes that “motivation causes a person to take action and represents the amount of initiative, persistence, and intensity of effort expended to achieve the desired outcome.” This effort means that decision making, driven by motivation is goal-oriented and, “essentially derives from people’s desires to satisfy basic common physiological and human psychological needs.”

As I wrote in my article Emergent Design,

“There are internal and external motivating factors. Internal motivation is influenced by our genes, health, sensory preferences, history of experiences, knowledge, and our sense of purpose in the world. External motivation includes incentive-driven factors (such as buying a house with a white picket fence), generated and manipulated by our families, communities, and culture. Combined, these shape our beliefs.

These attitudes are a collection of feelings and values based on a lifetime of experiences and education, which includes enculturated worldviews passed implicitly and explicitly as societal values. Most conditioned responses do not serve our authentic self-interests, the interests of our communities or, indeed, those of the planet. Many of our habitual behaviors and attitudes derive from illusion, judgment, attachment, aversion, addiction, habit, re-stimulation, assumptions, and unwarranted expectations. Assessing these patterns and worldviews help determine what and who is in the driver seat of design choices.

The more we derive our decision-making from conscious personal motivation, the more we can develop an awareness of and a drive for self-actualization. Through this self-fulfillment, we can maximize our potential as human beings. To do this, however, we must identify and unlearn counterproductive attitudes that developed through negative conditioning. Engaging consciously through goal-setting, and through applying transformational thinking and action, creates a broader awareness and confidence in one’s abilities while dissolving barriers and unhealthy patterns.”

Practicing decision making refines our ability to perform successfully. The more we skill up as designers, the more we can reprogram our response patterns and be useful in co-creating the world we live within. There’s a scientific article by Jason Shen, called Why Practice Actually Makes Perfect that explains the transformations with our brain’s neurocircuitry from practice. We can genuinely reshape and redefine our patterns and even reprogram our minds.

Undoing Harmful Social Conditioning

If we want to be more efficient and less influenced by enculturated and conditioned worldviews that aren’t serving us, evolving our design skills certainly gives us an opportunity to practice the kind of reflection and observation that’s required.

What are these enculturated and conditioned worldviews? In my 2000 MSc paper on Need Satisfaction, Well Being and Consumption I concluded that our current capitalistic society deconstructs our sense of identity by making us autonomous individuals incapable of meeting our most basic needs. Societal norms control the populace by fragmenting us from our social and ecological context and filling us with a never-ending pursuit of need satisfaction, including prescribed distractions.

We no longer feel integrated or empowered because of the fragmentation from our sense of resiliency as communities and connection with nature. We are conditioned to think that we cannot meet our own basic needs for survival without a robust centralized system of control that dominates and oppresses us. It’s the refined art of domination and subordination through fragmentation. For example, we have dozens of different types of specialized Doctors to care for our bodies and specialists to fix all our things.

This fragmentation and lack of context shape our identity. We become isolated and dependent, yet are taught to idealize individualization and privatization. This domination and subordination get perpetuated through media propaganda and conditioning. Those in power reinforce our beliefs and attention through news coverage by selling us need satisfaction hidden in the purchase of commodities. We get stuck in a vicious cycle of unproductive patterns (working to pay for education, insurance and health care for example). Mass media manipulates us through fear and distracts us with entertainment, and even goes as far as pitting subcultures against one another (such as racism, sexism, and by focusing on issues like pro-life versus pro-choice).

Naomi Klein in her book The Shock Doctrine — the rise of disaster capitalism, shines a light on this type of controlled distraction. She explains, “societies are deliberately manipulated into states of chaos through prescribed ‘shocks’ so that unpopular legislation and power gathering can slide through without resistance. It works because the population is diverted with the chaos.”

To dismantle this vicious cycle of oppression, we must become actively and consciously engaged. As my colleague Andrew Langford author of Project and Design Thinking, an online course, shares we no longer have to be, “servants of circumstances.” We can take charge of all the aspects of our sphere of influence. This deconstruction process requires un/learning, reprogramming, and active designing. Here are some benefits of becoming a conscious designer that Andrew and I have identified:

- Observing and understanding the motivation and need satisfaction

- Reconnecting to a sense of self-empowerment and confidence

- Increasing your ability to meet your own needs

- Liberating the skillful creator of your personal experience

- Reconnecting with community and nature

- Making decisions that are authentically in your best interest, rather than conditioned responses.

- Learning and affirming healthy and authentic patterns of behavior

- Generating more world-centric awareness

- Skilling up in conscious engagement and mindfulness practices

The act of designing can become an integral part of our everyday lives and way of thinking, and it can make a huge difference in how we succeed in the world as individuals, communities and in our interaction in and with society and the planet. The more we understand how to apply design, the more it becomes second nature. Design skills can become unconscious once we master them. Let’s now take a look at how our design thinking evolves to develop this skill.

Types of Design Thinking

Designers use thought and feeling to generate interventions in life and find desirable outcomes or solutions. Design thinking is said to utilize a combination of logic and reasoning with imagination and intuition, to explore possibilities and create desired results. Design thinking as a field refers to the cognitive activities that designers apply while designing. Cognition isn’t just thinking as it includes our perception, insight, learning, and discernment.

This term ‘Design Thinking’ is commonly referenced and used in the field. However, the design is so much more than just thought. Positioning intuition within the concept of thinking feels slightly prickly to me. I imagine an analytically minded person made that classification and it stuck. Perhaps we can rename the term ‘Design Practice.’

I first learned about design by studying ecology. Permaculture is an example of design practice that originated via ecologically literate thinkers, feelers, and doers. I define Permaculture as a whole-systems design approach that utilizes patterns found in nature to create human systems. Whole-systems thinking, another field, also called “systems thinking” — is a holistic type of decision-making that looks at the interrelationships and interconnections of the elements of a system rather than singularly viewing the parts as autonomous. The field of whole-systems thinking also integrates analysis and intuition.

There’s that word thinking again — hard to escape! I’d love to rename the entire field Whole-systems design or something. I won’t rename it though. Not here. Just know I want a different word. The term ‘thinking’ merely is not holistic enough for me. Consciousness is greater than thought.

Many Psychologists and ancient Asian philosophers often refer to two ‘thinking types,’ which I’ll call ‘states of being,’ analytical and intuitive. Analytical includes controlling, logical and critical thinking, problem-solving, reading and writing, calculation, processing information, and comprehension. The opposite type is more intuitive analog functions, which control senses, creativity, processing feelings and creative artistic inspiration.

In his article Analysis and Intuition, Charles B. Parselle says, “Analytical thinking is powerful. It is focused, sharp, linear, deals with one thing at a time, contains time, is deconstructive, contains no perspective, is subject to disorientation, is brain centered, and tends to the abstract.” He goes on to say, “Intuitive thinking has contrasting qualities: it is unfocused, nonlinear, contains ‘no time,’ sees many things at once, views the big picture, contains perspective, is heart-centered, oriented in space and time, and tends to the real or concrete.”

That’s very helpful to contextualize, yet is intuition really thinking Mr. Parselle?

When we look at how people approach design, there are three types of engagement: analytical, intuitive and integrated (harmonizing the previous two). The focus of the remainder of this section is on moving design towards an integrated approach, as it is currently very analytically dominant.

Both analysis and intuition bring a unique set of skills to design and decision making, including unique conditioned behaviors. From my experience working in the non-profit and higher education sectors, the two most common design approaches historically can be a degree of predict and control, and people using no system at all. “Predict and control” is a type of thinking that emerges from too much analysis. This decision making utilizes conscious planning that doesn’t include the un/learning and assessment of motivation, intuition or agility. My Gaia University colleague Andrew Langford and I use these design types to assess and support our students in their evolution as designers.

In his book Holacracy, Brian J. Robertson writes, “This industrial-age paradigm operates on a principle I call “predict and control”: they seek to achieve stability and success through upfront planning, centralized control, and preventing deviation.” Much of this predict and control style decision making is uninformed and based on preconceived expectations and conditions. However, the decision makers may apply design techniques to manage their process, yet the relationships and outcomes are often disconnected. This fragmentation leads to many of the problems of the world.

Another unfortunate outcome of over-analysis is paralysis. A designer or group of designers will spend so much energy trying to predict scenarios that burn out, lack of inspiration/engagement, or lack of focus/implementation often results. Also, with so much attention to analysis and design, the investment of energy usually causes people to control the outcome without being responsive to real opportunities and constraints that arise.

We also must remain aware of another issue, Silo Mentality. As defined by the Business Dictionary, “Silos are a mindset that perpetuates compartmentalization, where certain departments or sectors do not wish to or have no incentive to share information with other departments or on other teams.” This separation creates fragmentation and reduces efficiency, morale, and may contribute to the demise of productivity.

Finally, over analysis leads to over fragmentation, labeling, and objectification. This tendency is why I am suggesting that a very analytical person likely created the categorization of intuition as a thought process. Oh and by the way, if you haven’t picked up on it yet, I think the entire field of design is a bit over complicated and underwhelmed by analysis.

On the other side, being overly intuitive also has its issues. For one, it leads to not using design approaches or thinking at all. We already discussed the implication of conditioned decision making in the previous section. It can be quite oppressive if the person isn’t applying un/learning processes and assessing motivation for decision-making.

Langford, an expert in the field of un/learning, says, “Another concern with intuitive thinking is that it dismisses analysis as mechanistic. There’s rebellion against analysis in people who have heightened desire for artistic expression or who detest the industrialized culture that formulated much of our current day analytical thinking constructs and caused many of our current day social and ecological issues.” Having an obsession with deconstructing all previous systems and hierarchies is another trait.

Intuitive thinkers also relate intuition to magic and avoid analysis because they don’t want to break the energetic flow. However, this can sometimes cause self-asphyxiation or a case of bespelledment. The result is often not much result at all. A lot of procrastination, lack attention, and lack of motivation occurs with over intuitive types. They crave and attach to a specific feeling, and when that sense isn’t present, it’s often hard for them to flow or function creatively. Writer’s block is an example.

There is, however, a benefit of being able to make decisions at the moment using our intuition. In the article, Don’t Overthink It, Jocelyn Glei explains how the brain functions in an ideal state when we make quick decisions. According to her, adequate solutions rather than optimal solutions lead to more happiness. So “analysis paralysis” has an energetic cost and “quick and dirty” might be more fun. The article also explores how less is more, because rapid cognition streamlines brain function. This increase in effectivity means a yes to rapid prototyping.

In the article Implication of Intuition for Strategic Thinking, the author’s highlight that intuition derives from experiences. Our gut reaction, or that part of our brain that makes automatic decisions, that conditioned response discussed earlier, is part of the intuitive mind. The authors discuss military style strategic thinking, which led me to consider the famous book Sun Tzu’s Art of War. An article on Automatic Decision-Making looks at Tzu’s principles for being present in the real world, which inform the study of naturalistic decision making or recognition based decision making. Both help us understand how people make decisions in demanding real-world situations. Tzu’s work shows that in a war we have no time for logic. We need a situational response. Our brain functions in if/then statements, called symbolic logic. So here’s an integrative hinge point. In high demand situations, our intuitive brain utilizes symbolic logic which is primarily coded data.

Through practice, we can train our mind to have a matrix of pre-programmed responses. Our reactive brains are not wired for analysis driven adaptive behavior. However, analysis plays a part in making sure we program our brain with the situation responses that most serve our interests, and the broader eco-social context that influences and is impacted by our choices. So our “in the flow” sensation feels good and has a whole systems approach.

Eckhart Tolle — the author of the book, The Power of Now — is a great example and master of cultivating this “in the flow” state of mind. The book emphasizes the importance of living in the present moment and releasing thoughts of the past or future, which activate the pain body or conditioned mind. There are some critiques of Tolle’s work, such as The Failure of Now, by Nathan G. Thompson, which goes into detail about how Tolle’s work doesn’t address some of the eco-social systemic issues that plague the world. It goes into a discussion on capitalism, colonialism and the commodification of spiritual practices. The critique promotes critical consciousness, which I will make synonymous with using the analytical mind to address systemic issues and how they perpetuate patterns of injustice and deliberate oppression. Daniel Schmachtenberger in his talk Emergence shares about how we have evolved to use both analysis and intuition and by ignoring the past and future, we are not able to tap into our real self-actualized potential.

Thompson ends — and I agree — social activists often lack Tolle’s skill set of joy, stillness, and presence, and are instead reactive, ego-driven and have un-examined motivations. The author says, “Instead of figuring out how to place the outrage, sadness, and fears into the furnace, where they might be transformed into wisdom and wise action, too often social movements either explode or sputter into the ground through power grabs, ego battles, and undigested patterns of greed, anger, and hatred.” To me, I’d expand on this author’s insight and say that we need analysis to understand and respond to systemic problems, and to deconstruct our own internalized oppression by reprogramming our situational response patterns. We also need Tolle and other authors like Otto Scharmer’s description of intuitive presence, because ultimately that is where our brain is thriving in the moment.

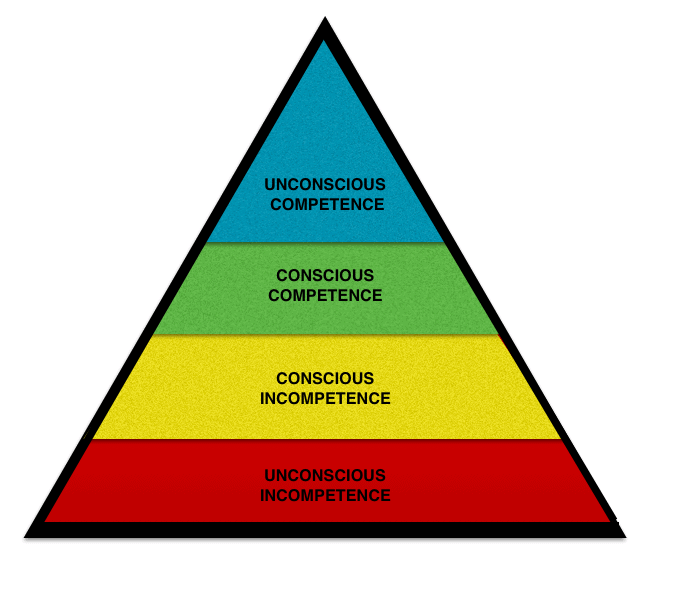

Noel Burch, of Gordon Training International, developed the above Hierarchy of Competence model, building on the work of Abraham Maslow. The four stages provide a model for learning as it suggests that we are initially unaware of how little we know, or unconscious of our incompetence. Through observation, we can become aware of this incompetence and start acquiring new skills. Eventually, we consciously apply this understanding. When we get to master the skill, we are in the flow, and we utilize our tools without thinking. This final stage is unconscious competence.

Design requires an awareness of the gaps in our competency, a refined mastery of being dynamically present, and continual un/learning. If the designer advances to unconscious competency, it’s important to continue practicing and explicitly articulating the design process to avoid getting stuck or overlooking essential design variables, as each design is unique and requires a fresh approach.

Design Field

The origins of design as a field were birthed from analytical reasoning to serve the fashion, graphics, industry, architecture, and product development fields. Its roots, some would say, are a response to material culture. However, philosophers have been postulating theories in publicly shared writing on design and designers of nature, and the speculation or identification of free will since at least Cicero’s book De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of Gods) in 45 BC.

Let us keep in mind, though, that much of our access to ancient or even modern theories on design are contained within our privileged society, dominated by an elite patriarchal class. This privilege means that more diversified origins and application of design as a science for co-evolutionary manifestation are not as easily accessible. White males dominate the field. There is not one woman or person of color listed as impacting the field of design thinking until after the year 2000.

There is a massive gap in the field historically that doesn’t encompass cross-pollination from different races, cultures, classes, nor the voices of women. This predicament is quite concerning given that design is so fundamental to life. I encourage you to read my article on Emergent Design, which unpacks the structural patterns of design all the way down to DNA. You may finish reading that article and realize that we need the voice of women and nature wisdom keepers to interpret and transform the field of design.

Even in the holistic field of Permaculture Design, this gap is still an issue. Karryn Olson-Ramanujan, a Permaculture Designer, says, “Though women receive the majority of all college degrees in the U.S., and are well represented in the workforce, they are very under-represented in positions of high-level leadership. Most of the women I’ve encountered in permaculture note analogous patterns: often, women constitute 50% or more of the participants in Permaculture course, yet occupy disproportionately few of the positions of leadership and prominence in lucrative roles, such as designers, teachers, authors, speakers, or permaculture superstars.” Part of our forward momentum in co-creating the field of design will be a tiny bit of deconstructing and decolonizing its roots, while also honoring the full pathway of evolution, moving towards a whole person/whole system integrative emergent design process.

If we don’t address the religious and spiritual evolution of humans as active thinkers and feelers and address the gender, cultural and whole-systems gaps in the field, we fail to grasp the scope and power of design as a knowledge base. It is not just the models and tools used by male-dominated professions of architects, graphical artists, and software designers. Religious teachers, philosophers, and spiritual writers and doers around the world have been addressing design for a millennium. Every gender, religion, race, and class designs — because to design is to be human. The philosophical proponents of the design of everyday life are an essential consideration for the field, as we all have the power to create compelling designs that impact the cosmos. That’s quite lofty.

On a more practical note, within the current recognized field of design, there has been a recent shift away from fixed planning with tightly defined goals, as designers have become more holistic and integrative in their approach. There are also more and more women adding their voices to design as a field.

As discussed earlier, predict and control style designs often create failed results with out of date thinking and burned out relationships. Also, on the other side, no design approach often establishes no effect or progress and perpetuates conditioned negative responses. Neither are sustainable or life-affirming. Our aim then is to understand that design is on an evolutionary journey towards combining analysis with intuition.

Technically, the transition from predict and control shifted first to log-frame designing, which was at least holistic in its attention to engaging in a full design process that included responsiveness through feedback loops integrated at the end of phases, and later added ongoing management and tweaking. Now the transition is towards more flexible and agile and iterative processes. In my article, Permaculture and Emergence: An Introduction to Design, I compare log-frame and agile design, while introducing Emergent Design as the direction and evolution of the field of design.

An article on Whole-Systems Thinking summarizes my thoughts about combining an integrated approach. The authors Gordon and Presley state,

“These problems cannot be solved in isolation apart from their impacts on the rest of the system; and the attempt to craft isolated solutions only leads to greater problems elsewhere. In a very real way, it is this old approach to problem-solving that has created the perilous predicament in which we find ourselves today.

Whole-systems thinking, by contrast, mimics the behavior of natural systems, which adapt to changing conditions in a flow based on outcomes that benefit the whole. It is important to stress that whole-systems thinking is a methodology, not an ideology. It is process-based rather than prescriptive. Its goal is resilience and adaptation rather than the achievement of a defined set of goods. Whole systems thinking adds shifts in perception, movement from parts to a whole, from object to relationships, objective knowledge to contextual knowledge, quantity to quality, structure to process, and contents to patterns.”

In summary, design as a field is shifting more towards agile (intuitive) rich approaches and also into whole systems or emergent design approaches (integrative). There is even a field of study called Integrative Thinking defined as “the process of integrating intuition, reason, and imagination in a human mind to developing a holistic continuum of strategy, tactics, action, review and evaluation for addressing a problem in any field.” We have Permaculture and other similar ecosocial fields to partially thank for this shift.

Now we need to redefine that word thinking. Systems Thinking, Whole-Systems Thinking, Integrative Thinking. None of it feels very holistic. What do you think and feel it should be?

There’s a lot more to consider and do to create meaningful change. This article is meant to elicit your thoughts and feelings. I aimed to encourage you to notice the gaps in the field and within your design practice. I’ll leave you with a few quick tips on cultivating a Designer’s Mind and some suggestions for further foraging.

Five Practices for Cultivating a “Designer’s Mind”:

1. Anchoring — Create a routine space for life to emerge by finding moments of stillness. A great place to connect with this silence is by sitting in nature.

2. Presence — Practice mindfulness in everyday moments to cultivate presence. Create a ritual awareness when engaging in day-to-day activities like walking upstairs, opening doors, cleaning, watering the garden, etc.

3. Observation — Refine your ability to proactively accept what is arising in each moment, rather than resisting. Allowing and witnessing will create a powerful momentum. If you feed or resist judgment or negativity, it will persist.

4. Assessment — Use knowledge, language, time, roles and models as tools, but don’t be defined or limited by identifying with their meaning. Don’t get stuck in conceptualization.

5. Alignment — Recognize that many of your interpretations, judgments, beliefs, and motivations birth from thousands of years of complex social conditioning that resides within our ancestral DNA, impacting culture, your life experiences and family upbringing. Continually question your perceptions and motivations (through analysis) while at the same time dropping identification and expectations. Be sure your “Designer’s Mind” is in the driver seat, and not your ego, inner critic, judge or pain body.

Incorporating the cultivation of our ‘“Designer’s Mind” into our design practice allows us to harnesses the power of engaging clearly in an interconnected way as we use design models and processes fit for diverse cultures and times. We can access introspection and integration of our practice to design in a manner that is intentional and present. This authentic groundedness in and acceptance of what is emerging is the foundation for any change. We can use this awareness to reshape the field of design and the direction of our evolution.

Please check out these other articles I wrote on the subject of design:

- Emergent Design: Finding the White Tiger

- Permaculture and Emergence: An Introduction to Design

- Principles of Presence: Applying Permaculture Design and Integral Theory to Personal Development

- A Design Cycle Application ~ GOBRADIMET

Beyond these articles, I’m offering two additional videos and guided meditation. I highly recommend these resources for further cultivating the designer’s mind, as they will significantly assist you throughout the entire design process.

- Designing the Inner Landscape: 15-minute video on being a designer

- Inner Landscape Design Nuggets: 20-minute video covering 11-steps for intra/interpersonal design

- Guided Meditation: 33-minute video on cultivating presence