by Karryn Olson

In the Permaculture Design Course curriculum, a key module is “Design for Catastrophe.”

Put most simply, the aim with permaculture is to deeply consider: “What is vital for the health and well-being of the humans and lifesheds here, now and into the future?” and then use the process of design to put the structures and processes in place towards that aim.

In the design process, one of the things we do is identify which functions (water, energy, food, etc) are essential to well-being of the Whole and then we make sure each of those functions is met in at least two ways — so that if one fails, that essential function won’t collapse. We call this “design for redundancy” and it builds in resilience. I also find it useful to note any “keystones”… for example, though food is a necessity, we could grow it without energy, but we can’t grow it without water, thus water is a “keystone function” that requires particular thought and attention in our design.

Now let’s add in the next layer. In any given context, various types of catastrophic events are possible, likely, or even necessary (such as the need for fire in many ecological communities). Therefore, instead of putting our head in the sand, or hoping for the best, in a permaculture design, we list out the catastrophes, and then examine our design through the lens of each, so that we can either design to avert it, ameliorate its effects, or escape it.

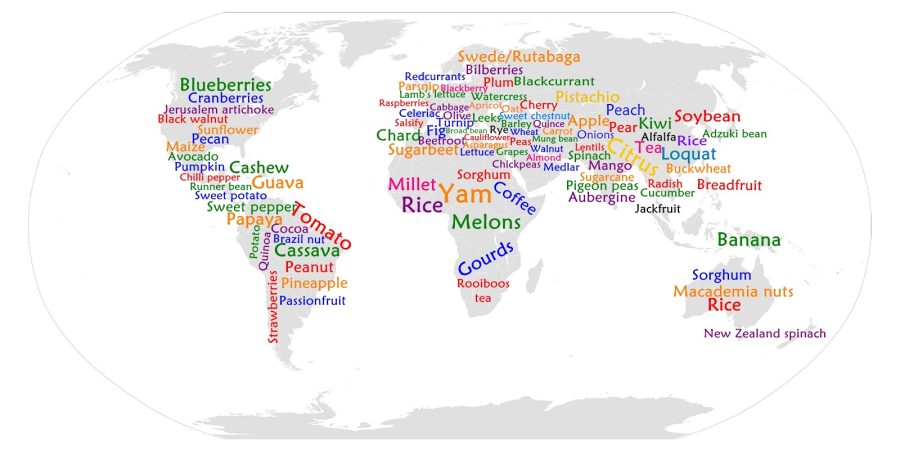

Commonly, in permaculture, we think of extreme environmental events: earthquake, hurricane, tornado, or other freak windstorms, flood, snowstorm, drought, fire, insect plague, etc.

But even at the home-scale, we should also design for social “catastrophes:” ruptures in relationships between life partners/family/neighbors; illness, injury or death that takes us (or a loved one) out of they system; unexpected caregiving demands; legal or financial setbacks; etc.

According to this concept, your home-based design is only complete when you’ve thought through the possible scenarios in your context, and done your best to design your site and human communities to fare as best as they can in that situation.

Of course, we don’t want to exhaust our mental health preparing for every possibility. Nor can we predict the future… the covid-19 pandemic—which has proved to be a global catastrophe on many fronts at once — has taught us that.

However, stress-testing our land-based and social designs through this “design for catastrophe” lens prepares us to be much more resilient and able to deal with novel, disruptive situations.

When designing for catastrophe related to our land-based design, here are some types of questions we might ask:

- What types of ecological disasters are likely in this area?

- Where is our social fabric vital, and what happens if this frays or breaks?

- Have we avoided placing our homes and families in the most disaster prone-areas?

- Are our homes built to shelter us in likely seismic or weather-related events?

- Do we have adequate and diverse sources of water, food, fuel, seeds, etc to get through emergencies?

- Do we know when we would need to evacuate, and have a plan?

- Have we made sure that several people know how to run and fix the vital systems so that we aren’t relying on one person in case they are not available, for whatever reason?

- Do we nurture a network of neighbors and friends for mutual support? Are we producing a surplus to share and redistribute?

- How might the failure of one vital element cascade and impact other elements?

- Are scenarios (fire) likely to snowball into additional catastrophes (like landslide)? What design imperatives arise from this?

Here’s the clincher: You’ll probably never regret having enough, learning how to think ahead, sharing and building relationships, or designing for the thriving of the lifesheds around you.

Equally important, this attention to home-scale resilience lends to community resilience, and community resilience can help with regional resilience.

Given our time when the number and intensity of ecological catastrophes is increasing due to climate disruption, these will likely be also precipitating wide-ranging social crises, like people being forced to migrate.

A truly resilient design considers the well-being of ourselves and our families, but then we network together to consider our communities, and our regions, with great care for planetary processes unfolding. For example, we should all be asking ourselves, “Is our region prepared to embrace climate or other refugees? What’s my role in that?”

Resilience in our Livelihoods

The principle of “Design for Catastrophe” also applies to our livelihoods.

Especially when we step off the usual mainstream career paths and don’t have access to the safety net provided by them: sick or parental leave, health insurance, retirement savings funds, unemployment benefits, etc.

To design for resilience in our livelihoods, a really useful framing question, “What is vital to the health of a regenerative endeavor, now and into the future?”

So far I’ve identified:

- Our own Health & Energy

- Creativity & Growth so we can offer great value to those whom we serve while also evolving ourselves to better serve the Wholes in which we are embedded.

- Time to do the work, and replenish ourselves, aiming for thriving, not just surviving.

- Cash Flow is the life blood of a endeavor in the form of money needed to live and work within the mainstream economy. We aim to tend it mindfully and skillfully.

- Social Capital is the is the life blood of a endeavor in the form of relationships. We nurture these with care.

- Systems & Structures enable us to set up healthy boundaries so we can minimize time on the tedious but required work. This enables us to focus on our high-value contributions, and also delight the people who pay us for our good work.

Each is critical, and all are necessary.

Design for redundancy!

Also, each will ebb and flow, but must be present in adequate quantity and quality, so set up cycles to reflect on and nourish each one.

You probably never regret having enough of any of them.

Bootstrapping = Lack of Resilience

My favorite definition of entrepreneurship is “a person who starts a venture assuming full risk of failure or success,” and it underscores that it includes risk at its core. This is true for social entrepreneurs starting a non-profit, as well as people doing regenerative work through a for-profit structure. That’s why I often use the term “endeavor” in this article.

Either way, most of the folks I know who are on the regenerative right livelihood path are doing it on their own, or with a very small team, so they are what is termed “micropreneurs,” and these folks are often bootstrapping — meaning that we make just enough money to put it back into the biz to grow it iteratively.

Bootstrapping is a great approach that starts where we are, and relies on our creativity instead of financial capital, but often leads to some combination of the following: We wear all the hats and do all the things. We work a LOT. We might not pay ourselves adequately so that our expenses for our biz are covered, and we are just getting by month-to-month. We can’t yet to pay for robust systems to support our work, so we cobble together good enough systems to get through. We don’t have time to really nurture relationships with potential customers or partners who might refer folks to us, so we don’t have enough clients yet…

You’ll notice that this approach to a livelihood is already not resilient, and therefore even small setbacks can lead to failure. That’s what makes entrepreneurship risky, and that’s why so many people who start an endeavor aren’t able to see it through. Too often, it’s only after livelihood gets “traction” in the market place and begins to have a steady stream of clients and revenue that we can put money into the other elements that are vital to the health of a livelihood.

These questions aim to help you design for resilience in your livelihood:

- Every day, am I remembering: “What really matters?” and “Why I’m doing this work?”

- Am I “being” who I need to be? Am I thinking and acting regeneratively? How do I nurture my growth edges?

- Do I choose the strategies, projects, and tasks to focus on what really matters?

- Do I have adequate downtime for replenishing, and to explore my creativity?

- Am I considering time and energy as precious, non-renewable resources?

- Does pricing nourish my endeavor and myself?

- Am I nurturing my social capital in a sincere, and ongoing way? Am I in integrity in my relationships?

- Am I designing for the full cost of treating myself well as an employee of my business (i.e., funding my retirement and health insurance or deductibles etc. that I will need to cover)?

- Do I consistently look for ways to set up systems and structures to free up my time, serve my clients better, and cover my ass?

Now, let’s circle back to the concept of “keystones” in the first section of this article.

Of the six elements that are vital to the health of our regenerative endeavor, are there any you identify as a “keystone function” and deserve extra care and attention when designing our livelihoods?

Catastrophes Happen in Our Livelihoods

I wrote this article to digest my learning from a recent personal “catastrophe” in my livelihood.

In November of 2020, I lost all vision in my left eye, and had to have laser surgery, and then — a week later — another eye surgery to restore my vision. Of course, this meant I had to also take several weeks to recuperate, and cancel everything in my calendar, including outreach and re-launch of all my courses that were slated to open to new members around that time. I also had to mentally and emotionally process this setback.

It’s easy to see how running out of health, meant I also ran out of energy, and time all at once.

But I could rely on social capital — my clientswere understanding and supportive and I could easily connect with them through the systems I’d built. I also could call in the my trusted biz coach to help me think through what this wake-up call means for my business. I could then change the structure of my business model to honor my need to better reflect my need for more rest. I used this opportunity for growth to get clear on what really matters, and got to see that the leading up to this eye thing, the need to “get shit done” was draining my creativity.

Yes, friends and family came through for me, but with covid, it made it especially hard to rely on even the closest, most robust social capital.

There was no money coming in, but the platforms and email software that serve my clients needed to be paid for, as did my coaching session, and help to do the visually-intensive work that I couldn’t do for a few weeks. Not to mention the out-of pocket costs for the surgeries themselves. Crowdfunding is the only form of social capital I can imagine that would have paid for those things, so cash flow became a “keystone function” in this scenario.

Because of a recent house sale due to my divorce, I’m in the very privileged position of having some financial cushion. But if that relationship “catastrophe” hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have had this cash reserve. On the other hand, the divorce also means I will be paying out of pocket for my health insurance and deductibles, and funding my own retirement, among a sea of heartache. That’s why the “breakdown of relationships,” in my humble opinion, go on the list of potential catastrophes. Even if they are mutual and for the best, they often necessitate a complete restructuring and/or loss of the systems built so far.

All this got me thinking of the “Design for Catastrophe” principle, and how this applies to our livelihoods. I share these insights in the hopes that they help you design a resilient, thriving livelihood.

Here’s a beginning list of questions to stress-test your livelihood endeavor:

- Have I listed and considered the potential livelihood “catastrophes” in my context? Am I designing with them in mind?

- What if I can’t work for a few weeks? Months? Do I have enough money to get me, my beloveds, and my business through?

- If I don’t touch my biz for a month or longer, what parts would collapse? Which would still function well?

- Do I know what I need to do to cover my ass? How can I find out? And, am I setting up systems so this can be done efficiently? For example: Where am I exposed legally? or How can taxes be easy?

- Am I keeping in mind my future (i.e., funding my retirement and health insurance costs, etc) as I build my livelihood now?

Beyond our individual endeavors, I believe that setting up systemic structures which support regenerative entrepreneurship are key for shifting towards a regenerative economy. I’ll share and invite dialog about that in a separate article.

What would you add as an answer to this question: “What is vital to the health of a regenerative endeavor, now and into the future?”

Did you identify any “keystones” in the list of elements that are vital to the health of a regenerative enedeavor? How are giving them special care?

What would you add to the list of questions for “stress testing” your livelihood to design for catastrophe?

If this article was helpful, consider clapping (you can clap as much as you want, up to 50 times) or sharing. Thank you!